Leona

Chalmer's 1937

book with a

drawing of a cup.

And

read comments from people who have

used a cup.

Do cups

cause endometriosis? Not enough evidence,

says the FDA.

|

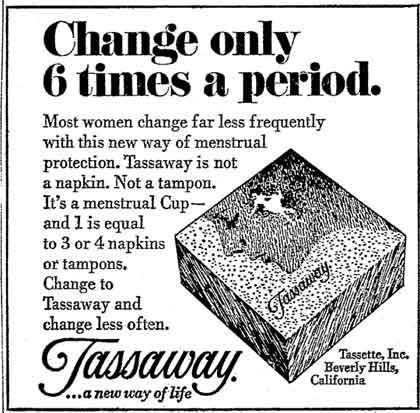

A History of the

Menstrual Cup (continued)

Women Tossed Away

the Tassaway

Below: a newspaper Tassaway ad

from its first year, in the Reno

[Nevada] Evening Gazette, November

4, 1970. More ads: 1971 and 1972, 1972

& 1973

Dutch ads, and instructions

for

use of the cup.

|

|

Below:

The Tassaway mark in the U.S.

Patent and Trademark Office, filed

Aug. 9. 1966 but described as

having been in use since 1963.

|

|

It's a short story. It's a short story.

In 1970, Tassette, Inc., the

maker of the now-defunct Tassette

menstrual cup, launched its first

promotion since the early 1960s,

this time for its new disposable

cup, Tassaway

(bottom of page), which was

made of a non-absorbent

elastomeric polymer (patent

drawing at left). Robert Oreck,

the president of the company,

hoped the new cup would generate

more money than the old one by

solving the two problems Oreck

thought were at the heart of the

failure of Tassette: women did not

want to wash and re-use the cup,

and satisfied customers would

not quickly buy another one

because they could use them for

several years.

Eduardo F. Peña, M.D.,

Fellow of the American College of

Obstetricians and Gynecologists,

tested the Tassette at the

company's request in 1961 (the

journal Obstetrics and Gynecology

published his report "Advantages

of the Menstrual Cup" - Tassette,

Inc. funded the study - in the May

1962 issue), and talked with a

Barron's reporter in 1970 before a

talk he gave about Tassette (not

the new Tassaway) at the Sixth

World Congress of Obstetrics and

Gynecology.

Peña's judgment was

positive, including "[u]se of the

cup is hygienic in that it avoids

the infections commonly associated

with sanitary napkins and

tampons." What he meant were

mostly infections caused by the

Trichomonas vaginalis protozoan

(he said that Trichomonas caused

80% of vaginal infections he saw

in his practice in Miami) and the

Candida albicans fungus, which

causes moniliasis, which thrives

in Florida's subtropical climate.

Cystitis is also a problem with

women using pads, because feces on

the napkin can bring Esherichia

coli bacteria to the urethra.

(Read the Dickinson

Report from 1945 about these

very problems.) The doctor

recommended that users dip the cup

into a weak solution of chlorine

bleach after the period to kill

any adhering bacteria.

(In an article from the "toxic

shock era," which started with

menstrual products in the late

1970s, in Infectious Diseases in

Obstetrics and Gynecology

(2:140-145, 1994), Philip M.

Tierno, Jr., and Bruce A. Hanna of

the Departments of Microbiology

and Pathology of the New York

University School of Medicine,

wrote that "S[taphylococcus]

aureus MN8 produced no TSST-1 when

grown in the presence of

Tassaway," thus absolving Tassaway

of any charge of promoting toxic

shock.)

Barron's reporter Alan Abelson,

who wrote the column "Up and Down

Wall Street," criticized the

doctor's statement that the cup

was "an economically viable

product." He said it was a

judgment for the consumer to make.

He was only partly right. Suspicions of

fraud involving shares in the

company surfaced. (See a

share

from 1971.) Tassette, Inc.,

reported selling thousands of

Tassaways, but not nearly enough

to justify the high value of each

share.

On July 17, 1972, a federal

judge in Los Angeles issued an

order permanently enjoining Robert

Oreck and Tassette, Inc., from

violating the registration

provisions of the Securities Act

of 1933 and the anti-fraud

provisions of the Securities Act

of 1933 and the Securities

Exchange Act of 1934.

Interestingly enough, apparently

women could still buy the cup in

The Netherlands in 1972 and 1973,

as these ads here and

here

show. (More ads: 1971 and 1972,

and instructions

for

use of the cup.)

Tassette, Inc., was essentially

dead, but it had hardly lived.

Just as with Tassette, the company

never made a profit. The company

owed J. Walter Thompson, the

advertising agency, a little over

$1 million, while having assets of

only $228,829; a Tassette lawyer

lowered that value to $30,000,

partly because the unusual nature

of the equipment reduced its

attractiveness.

Not until the late 1980s did The

Cup reappear. This time it has

succeeded modestly. I'm talking

about The Keeper (Part 4).

(Most of

the information above about

Tassette, Tassaway and Chalmer's

patent came from Advertising

Age, Barron's, Drug Trade News,

Editor and Publisher, Investment

Dealer's Digest from the 1960s

and 1970s; and from a Stock

Prospectus dated 28 August 1961.

Mr. Oreck refused my request for

an interview, referring me to

another company official; I

could not find her.)

© 1997-2006 Harry Finley.

It is illegal to reproduce or

distribute any of the work on this

Web site in any manner or medium

without written permission of the

author. Please report suspected

violations to hfinley@mum.org

|

|