Read an earlier discussion of this: What did

European and American women use

for menstruation in the 19th century and before?

|

Some facts about European underwear, 1700 - 1900,

and its

relationship to what women used for menstruation

(Part 2, Part 3)

In brief - how's

that for a pun! - here's what I think:

In some societies today, women use no

special "device" to absorb or catch

menstrual flow - they simply bleed into

their clothing, even if they must stay in

a special place during their period (for

example, among a group

in India; I have heard stories about

others).

Apparently many women in certain parts of

Europe from 1700 to about 1900 also used

nothing special - not rags, not pads, not

sponges or anything else - during

menstruation, but bled into their

clothing. And, because most early American

settlers came from Europe, this suggests

that some (most? all?) Americans, and

probably Canadians, also bled into their

clothing at some point in their nations'

histories.

Read my grande finale conclusion, with

proof.

(All of the pictures and most of the

following information come from the

terrific catalog of the exhibit of the

history of underclothing at the Historical

Museum of the City of Frankfurt am Main,

Germany, in 1988: authors, Almut Junker

und Eva Stille [Almut is a woman's name],

Zur Geschichte der

Unterwäsche 1700-1960. 1988.

Historisches Museum Frankfurt )

In 1700 (and long before) women and men

in Germany and France, and probably other

European countries and America, wore a long shirt from

shoulders to calves,

a chemise

or vest (Hemd, in German; see the two bottom

illustrations on this page), next

to their skin, day and night, not

underpants and other items common today.

The rich and upper classes wore fancy

versions, the rest simple ones.

Only men wore pants

as outer clothing, a symbol of their authority

(in English we still say "so-and-so wears

the pants in the family," as do the Germans

in their language) although women would

sometimes wear versions of them next to

their body when riding or when the weather

was cold. Later, with the French Revolution

and afterwards, women started to wear

long-legged underpants to shield themselves

under diaphanous dresses, but it took

decades for such pants-like underwear to

gain wide acceptance among the upper classes

and even longer among the common people.

They continued to wear only the chemise

under their clothing for most of the 19th

century. Women who wore traditional regional

costume in Germany (and I bet elsewhere)

sometimes wore no underpants until the

1950s.

In 1757 a German doctor gave another

reason why women shouldn't wear pants or

closed underwear: her

genitals needed air to allow moisture to

evaporate, which could otherwise

cause them to decay (German, "vermodern")

and "stink." But he conceded that women

could wear them in cold weather and to

protect against insects. (Christian T. E.

Reinhard, in his Satyrische Abhandlung von

denen Krankheiten der Frauenspersonen . . .

Teil 2, Berlin/Leipzig, 1757, quoted in Zur

Geschichte der Unterwäsche 1700-1960.)

|

|

|

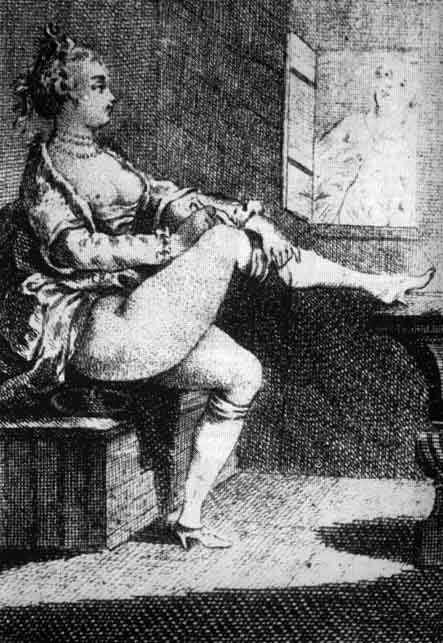

An 18th-century woman (this one

is from the upper classes) wore no

underpants, just a chemise

(long shirt) under her outer

clothing (you can see it run

horizontally right under her

breasts), like the common people,

as this engraving shows. She sits

on a toilet (Abtritt) while a man

peeps at her through the window.

(Copper engraving from the second

half of the 18th century, from

Volume 2 of Bilderlexikon,

published by the Institut für

Sexualforschung Wien, 1928-31, and

reproduced in Junker und Stille's

"Zur Geschichte der

Unterwäsche 1700-1960," 1988,

Historisches Museum Frankfurt)

|

|

|

|

A doll's chemise (Hemd), about

1785, from the underwear exhibit

in the Historical Museum of

Frankfurt (am Main, Germany), and

shown in its catalog "Zur

Geschichte der Unterwäsche

1700-1960."

|

|

Three patterns for women's

chemises - A and C "á

l'Angoise," B "á la

Françoise" - from

Françoise-A. de Garsault, L'Art de

lingére, Paris,

1771, reproduced in "Zur

Geschichte der Unterwäsche

1700-1960."

|

|

© 2001 Harry Finley. It is illegal to reproduce

or

distribute any of the work on this Web site in any

manner or medium without written permission of the

author.

Please report suspected violations to hfinley@mum.org

|