|

|

Some South American Indians, for instance, thought that all mankind was created out of "moon blood."

The Mesopotamian mother goddess Ninhursag was said to make men out of loam and her "blood of life." She taught women to make loam dolls for use in a conception spell by painting them with their menstrual blood.

In the Bible's "Genesis" the name Adam is derived from "adamah," which can be translated as "bloody loam."

|

The hieroglyph hsmn, menstruation, short version |

hsmn, the spelling of a later period (1) (see the numbered notes at the end of the article) |

Medicine [for a woman whose eyes] are bad so that she cannot see and whose neck hurts.

Then you should say: There is material in her eyes overflowing from her uterus.

Then you should do [the following] against it: you should expose her to the vapor of frankincense and fresh oil; you should expose her vulva to those vapors; you should expose her eyes to the vapor of oriole thighs, then you should see that she eats fresh donkey liver.

If you examine a woman who has had a discharge like water and the end of it is similar to baked blood, then you should say: This is a scrape in her uterus. Then you should make her: Nile earth from the water carrier, which you crush in honey and galena; put this on a dressing of fine linen and insert it into her vagina for four days.

If you examine a women who suffers from the side of her pubic region, then you should say: This is an irregularity of her menstruation.

|

Excerpt from the Papyrus Ebers, a transcription by Walter Wreszinski |

If you examine a woman suffering in her abdomen, so that the menstrual discharge cannot leave her; and you notice something in the upper part of her vulva: Then you should say: This is a blockage of blood in her womb.

Then you should make for her [a mixture of]: fruit (5), 20 parts; oil/fat, 1/8; sweetened beer, 40 parts; it should be cooked and then imbibed for four days.

Then you should make her a laxative for the blood: pine oil; caraway; galena; sweet, aromatic myrrh resin; it should be cooked until a homogeneous consistency is achieved and then her pubic region should be repeatedly rubbed with it.

Additionally you should administer hyena-ear (6) in oil/fat as follows: After it is rotten you should massage her pelvis region repeatedly with it. Then you should put some myrrh resin and frankincense between her thighs and let the vapours penetrate her vulva.

|

Image of a tyet taken from the Book of the Dead of Ani (ca. 1250 B.C.E.), British Museum, London |

Tyet-shaped wooden salve spoon with Hathor head, Berlin, Inv.Nr. 1178 (9). |

This is how a 4000-year-old invention looks today.

Tampons are almost as old as earth itself. Because there were always women who, of course, used an internal menstrual protection.

The first tampons were handmade from leaves or natural fibers. Today too tampons are manufactured from natural materials. But in contrast to the past an o.b. tampon is far more hygienic and reliable. Now we are able to make this great invention even better.

Every o.b. is covered with a very delicate, soft fleece. This makes it smoother and more able to slide. Therefore it can be inserted noticeably easier. Even for light flow or at the end of the period changing the tampon is very easy. So easy that today so many women think o.b. tampons are one of the world's best inventions.

o.b. - the small piece of additional freedom

Translation:

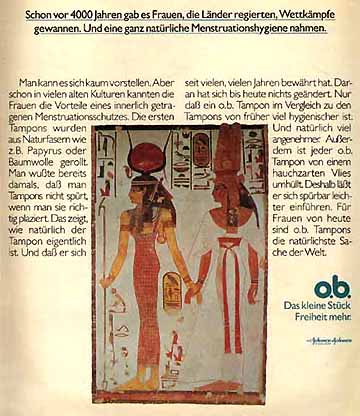

Four thousand years ago there were already women ruling countries, winning competitions. And using a completely natural menstrual protection.

It is almost unbelievable. But in many ancient cultures the women knew about the advantages of an internal menstrual hygiene. The first tampons were made by rolling up natural fibers such as papyrus or cotton. Women already knew that they couldn't feel them if they were inserted correctly. This shows how natural the tampon actually is. And that it has proved itself for many, many years. Nothing has changed. Only that an o.b. tampon is much more hygienic than the earlier ones. And of course more comfortable. In addition, each o.b. has a very thin fleece covering. Therefore it can be inserted noticeably easier. For today's women tampons are the most natural thing in the world.

o.b. - the small piece of additional freedom